Writing Women in to History

I remember my 10th grade history teacher saying to all of us, go make herstory. I have often thought about this comment throughout my life.

I went to an all-girl, Catholic high school. I think some people, in today’s politically charged environment, would think of herstory as a liberal concept. But the teacher was not liberal and her point, about men writing history, and leaving women out of the story, is not unjustified.

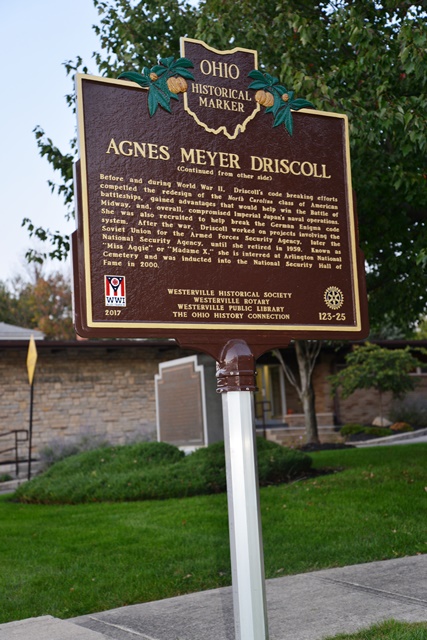

For example, I have read many articles and books about cryptography, and in all of my readings, I never came across a female cryptanalyst named Agnes Meyer Driscoll, until I was in Westerville, Ohio, and I happened upon Agnes’s house, which was marked by a plaque. I was truly surprised that she is known to be one of the top cryptanalyst.

So who is this remarkable woman, which actually helped the United States during World War I and World War II?

Agnes was born in Geneseo, Illinois, July 1889. Agnes’s father moved to Westerville, Ohio, for a teaching job, in the music department, at Otterbein University, in 1895. Agnes was 16 years old, at the time; she would complete her high school education in Westerville. After graduation, she attended a business school in Amarillo, Texas, and then went to Otterbein University, from 1907 to 1909. She went on to The Ohio State University in 1910, graduating in 1911 with a Bachelor of Arts in mathematics and physics. She also studied foreign languages; mastering French, German, Latin and Japanese. Agnes also studied music and statistics.

After graduation from The Ohio State University, Agnes would teach music at Lowrey-Phillips Military School in Amarillo from 1912 to 1915. In 1915, she would accept a job to chair the mathematics department at a high school in Amarillo, where she would stay until 1918.

In 1918, America had just started to allow women to enlist in the armed services, thus she would join the United States Naval Reserve as a Yeoman 1st class. She reported to active duty at the Naval Yard in Washington D.C.; within three months, Agnes would be assigned to the Office of the Chief Cable Censor, were she did basic filing of telegrams. While assigned to the Office of Chief Cable Censor, she was promoted to Chief Yeoman. Agnes would be transferred to the Naval Communications were she solved all machine ciphers that were submitted to the Navy, to be used for communications. It is not surprising that none of the ciphers submitted for consideration would be used, since Agnes had found the weaknesses, in them all.

At the end of the war, she would be released from active duty but remained as a civilian at her post. Agnes became involved in more than breaking the ciphers; she actually ended up making a cipher machine. In the early 1920’s, there is a Naval record that states that Agnes would co-develop a cipher machine and the standard device used for enciphering for the Navy.

Agnes left the Navy for two years, after being offered a position, as a result of having solved a puzzle advertised as impossible. The private firm hired Agnes as a technical adviser for a cypher typewriter. The company would eventually fail, but the concept of rotor technology would impact future designs of cryptographic machines.

Agnes returned to the Navy in the spring of 1924 and would marry a Washington D.C. lawyer named Michael Driscoll.

In 1926, Agnes along with another colleague would break the Japanese Naval manual codes and would continue to break Japanese code each time the Japanese would release a new manual. She would have another unexpected break from the Navy, after she was in a severe automobile accident in which she broke both her jaw and leg. The car accident was in October of 1937 and she would not return to work until September of 1938. Her leg would never heal properly, and at 48 years of age, she would use a cane for the rest of her life. When she returned to work, she continued to work with the Japanese Naval code, but would be pulled off that project to work on the Enigma, and we all know how that turned out – but did you know of Agnes Meyer Driscoll’s input?

Sadly, Agnes was not inducted into the National Security Agency Hall of Fame until the year 2000. Like so many other woman in history, her story has barely been told. It must be our job, as enlightened men and women, to make sure that when future generations are learning about all of the remarkable men who have made a contribution to keeping us Connected, that we also tell them about the many women who with pencil in tow, stood shoulder to shoulder with their male colleagues, conquering the challenges placed in front of them in making herstory. Let us all stay Connected.

The Historical Marker

Her Home