My Thoughts

But Mostly His Words On

Waiting for Snow in Havana

Confession of a Cuban Boy

By

Carlos Eire

“Looking the teacher straight in the eye, Miguel answered: ‘Columbus said, ‘This is the most beautiful land ever seen by human eyes.’”

“Excellent, I’m glad to see not only that you were paying attention, Miguel, but that at least some of you have had a proper upbringing and were told about this at home, before we got to today’s lesson. You know, what Columbus said is very, very important. It may be one of the most important things ever said about our island, one of the most true.”

“Yes, Cuba is a paradise.” said Ramiro, unbidden. He was the one who had been holding his arm up higher than anyone else. ‘My dad told me that the Garden of Eden was here in Cuba, and that Adam and Eve were not only the first humans, but also the first Cubans, and that the entire human race is kind of Cuban. And he also said that this is the reason we don’t have any poisonous reptiles at all.’”

“True, Ramiro, Cuba is a paradise, and it very well might have been the original Paradise, the Garden of Eden. How many of you have heard this before?”

I apparently lacked a proper upbringing; it was not until I began to read this book that I heard the notion of the Garden of Eden being in Cuba; though in retrospect, when my parents spoke of Cuba, including my American Mother, and those Cubans of their generation, they did speak of Cuba as a paradise, all be it a lost paradise.

On page one of chapter one, Mr. Eire begins his book with the words: “The world changed while I slept, and much to my surprise, no one had consulted me. That’s how it would always be from that day forward.” He continues on that page, speaking of his mother:

“Maybe she dreamt of hibiscus blossoms and fine silk. Maybe she dreamt of angels, as she always encouraged me to do, ‘Suena con los angelitos,’ she would say: Dream of little angels. The fact that they were little meant they were too cute to be fallen angels.”

“Devils can never be cute.”

I looked around the room and desperately wanted to read those words to someone and discuss the notion of little angels being good and devils not being cute. Another fail in my Cuban education; did all Cubans believe in good little angles and devils only being ugly? Yes, before you get upset, I only believe in one devil, but he does have many demons working for him, they too must be ugly.

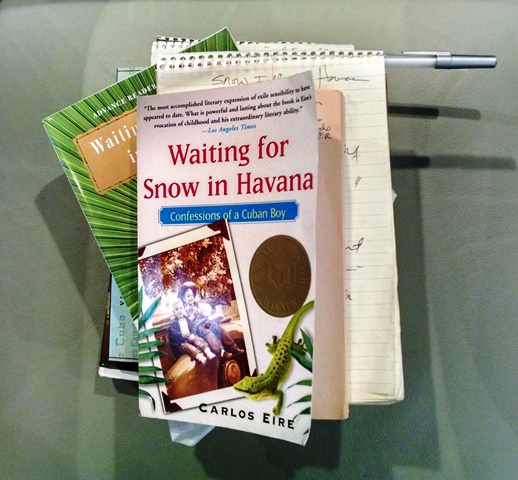

Months ago, I promised the copy of Waiting for Snow in Havana, which I was reading, to Marcial, sure that he would actually read it, if I gave it to him, and certain it would have some impact on him, though not the impact it has had on me; rather the impact appropriate for his reality.

The truth is that I will not be giving him this copy, though Kate has already ordered one for his Christmas box. Not only has my copy been maligned by the length of time and the many trips it has taken, as I have tried to read it; but the need/desire to write in the book overtook my good intentions, of making notes in a spiral notebook, and it is now quite filled with check marks, asterisks, and lines.

I have had this book in my life for a very long time. Originally, it was the Advanced Reader’s edition that I began to read; until I ran into a problem, I often have with anything written about Cuba, references to santeria, which normally causes me to throw the book away. But with Waiting for Snow in Havana, I put the book aside, deciding I needed to take a second look, at a different time; as the author’s remarks were unlike the offending references, in the past.

Mr. Eire manages a paradox that I find most Cuban, when dealing with the supernatural or spiritual; he manages to show both an irreverence and respect for the divine and religion, his references to the objectionable Cuban curse, in this writer’s opinion, are used to set the scene and explain the culture, more so than to propagate an agenda or glorify evil.

Reading his book, I was also taken aback, just a bit, by use of curse words, in a piece of non-fiction. Oddly, he too seemed to struggle with this issue, explaining it from a spiritual perspective, in terms of it being a sin and its impact on his soul.

However, that is the beginning and the end of my criticism for this book. Mr. Eire’s master of language, both English and Spanish, were a delight! I felt like I was feasting, at the most delicious of banquets, although undeniably a table set with more than a few bitter dishes; as the writer deals with his childhood and the events that led to him becoming one of the 14,000 children that took part in the Operación Pedro Pan, Peter Pan Operation, which brought unaccompanied children to the United States, from Cuba, to escape communism and the fear of children being sent to the Soviet Union.

This remarkable biography and book of history may not be for everyone, but I must say it has been a long time since I read something that I so wish I could discuss in a book club or at a perfect dinner party. I mean how can I read “Have mercy on me, Lord, I am a Cuban;” and not need to talk about it!

“. . . One of these sages was Saint Jerome, the man who translated the Bible from Hebrew and Greek into Latin in the fifth century. Legend had it that Saint Jerome used to say ‘Have mercy on me Lord, I am a Dalmatian, while he beat his breast with a stone, struggling to suppress his own will and make his soul ready for God’s abounding grace. What a wise man. He knew how deeply sin dwells in our skin. My own worst instincts still lead me to turquoise water, tangerine sunsets, and the judge’s seat. I, too, find myself clutching jagged chunks of granite, beating my breast, seeking redemption. But I have to make a slight alteration in Jerome’s prayer – a small change that makes a world of difference:

Miserere mei, Domine, Cubanus sum.

‘Have mercy on me, Lord, I am a Cuban.’”

The writer takes us into his life in Cuba, as a child, and shares with us the moment the Revolution becomes a reality in Cuba, and its impact on his world, with intimacy and heartbreaking detail, while still managing to show us the joy, love, and wonder in life, which help define him.

Obviously, the antagonist in this story is the evil that the Revolution and its perpetrators bring to Cuba, changing the author’s life irreparably, as well as more than a few of us. But his perspective is again that very Cuban quality of paradox, it is both deeply personal and yet universal, at least for those whose lives are crushed by loss from shattered dreams and realities, death and exile, hope and most poignantly, by the people that we love.

“My grandmother would discern very soon after he assumed power that Fidel was up to no good at all. She had a way to tell.

‘You know, that Fidel can talk for hours on end and voice all kinds of things for the future, but he has never ever said ‘si Dios quiere,’ not even once. He’s up to no good. He doesn’t know what he’s talking about, and is a fool. He may also be an atheist, and that can only mean trouble.’”

I have never read his grandmother’s perspective anywhere, in my studies; what a clear, simple, and yet profoundly accurate metric to assess Fidel; a man in whom so many put their faith, all be misguided.

“By 1959, at the age of eight, I knew I wanted to marry an American” woman, preferably one who looked like either Marilyn Monroe or Kim Novak. Meanwhile, nearly everyone around me was worshiping a man with a black beard whose name was not Jesus.”

Fulgencio Batista had been president of Cuba, from 1940 -1944; he then returned to power on March 10, 1952, through a successful coup, staying in power until January 1, 1959, when the Revolution triumphed, while Mr. Eire slept.

The tragedy of the Revolution in Cuba was immediately felt not only by Fulgencio Batista’s henchmen, of who there were many, but also by so many ordinary people who either disagreed with Fidel, or were seen as a threat to his power, or were simply the victims of some individual who suddenly had the power to exact revenge; whether the offence merited it or not, was unimportant. Not only were Cuban prisons soon overflowing, but Fidel instituted the death penalty, as punishment for those offences. (Prior to the Revolution the death penalty was only applied to treason and crimes associated with the military.)

The call “al paredón”, to the wall, to be executed, became an all too common cry; sometimes with a mock trial, other times, simply at the whim of man who had the power to bring death to a Cuban soul; though torture was not overlooked. (For those of you who adorn yourself with Che Guevara t-shirts, or think it was nice that President Obama posed in front of Che’s mural, you should understand that Che took great glee in instituting firing squads in Cuba, especially brutal at La Cabaña and Santa Clara prisons, murdering thousands of Cubans, whether they were guilty of a crime or not. Che said:

“To send men to the firing squad, judicial proof is unnecessary. These procedures are an archaic bourgeois detail. This is a revolution! And a revolutionary must become a cold killing machine motivated by pure hate. We must create the pedagogy of the paredón [execution wall].”

Mr. Eire, speaking of his cousin Fernando’s experience in prison

“You see, prisoners were also often forced to watch one another’s executions. So Fernando knew about the blanks, and about the shooting into the air, and the shooting to kill. He also knew about the real ammunition, and what really happened when someone was riddled with bullets. He knew that much too often the firing squad aimed to maim, not to kill, and they’d make the condemned suffer as much as possible before blowing out his brains, the so called coup de grâce.”

You may be ready for your coup de grâce; but beside the check marks, asterisks and lines, I did keep the spiral notebook with me, and filled it as I read, thus wrapping me this up is not easy. There is so much more I desire to share with you.

I have known for years that the Cuban government called the Cubans who left the island gusanos (worms), a name derived from the one piece of luggage, which they were permitted to take when they left; but I did not know that the bag was designed and constructed to abide by specific weight and content limits. I indeed found it fascinating what he was permitted to take, and the lengths his mother went through to acquire the bag and the stories of people’s bags being taken from them . . ., but none of that is why I feel I must include gusanos, rather:

“The bags looked like worms. Gusanos for the gusanos.

Very funny. Especially when you know that caterpillars are also gusanos. Everyone knows what happens to caterpillars.”

Oh my, what an amazing mind Mr. Eire possesses.

Or if you would like to understand why Cubans disdain the beloved Kennedy’s, by all means read what Mr. Eire says regarding the Bay of Pigs, where the brothers “nos embarcaron”.

“Years later, the truth would emerge. They did get screwed, after all. Those damn Kennedy brothers, John and Bobby, pulled the plug on the invansion when it was much too late to do so. Pulled the plug and left the men there to be mowed down, as the dogwoods and azaleas bloomed in Washington. They were only Cubans, after all.”

“And who ever heard of the good guys losing?” Sadly, Cubans, we know too well that good guys keep losing; while so many are blinded by false hope.

“Blame it on the sun, and the sunlight. It makes as much sense as anything. With all that light, Cubans have a hard time letting go. Even I they only lived in the place for one day before being whisked away, the sunlight is forever trapped in their blood. We love much too deeply. I see this trait in my half-Cuban children, full blown at times, and they haven’t even been to Miami yet.” That is all for now. At least until I read Learning to Die in Miami.